Ernesto Cavour and the Bolivian Charango

por

Víctor Montoya

(Translation by Elizabeth Gamble Miller)

The charango is an offshoot of the Spanish vihuela, which came to Dark-skinned America with the Conquistadores during the 16th Century, especially after the apogee of the legendary silver mines of Cerro Rico de Potosí. There, gentlemen with cape and sword, brigands, bohemians, and troubadours offered nightly serenades to women of high birth. As time passed, like an adventurer defeated in his search for fame and fortune, the vihuela was abandoned to its luck, and eventually fell into the hands of the indigenous peoples and those of mixed blood, who lost no time in converting it into a charango by dint of dressing it and redressing it, as Cavour says: "with wood appropriated from munitions boxes that came to the mines of Potosí, or from tins of alcohol, and–why not–also from gourds with a taste of chicha liquor and disillusions.” So it acquired a personality all its own, both in form and in sound, and became the most authentic cultural expression of native sentiments.

Even if some don’t believe or accept it, the cradle of the charango is in the Bolivian high plains, where its voice blows like the wind through the tall grass and its melodies disperse like carnations among the peaks of the Andean range. It’s not rare for a small, well-crafted charango to be a true work of art that, when its strings of gut, metal or plastic are plucked, emits a sound like that of a spring, so pure and harmonious that no voice in the world is superior or equal to it.

The Bolivian charanguero, throwing himself into his profession and giving his imagination free rein, makes this object of five double strings, rounded frame, and feminine silhouette more sonorous than the mandolin, the tiorba lute, the balalaika, and other instruments that envy it for its variety and resonance. As if that were not enough, since the 30s of the 20th Century, Master Mauro Núñez, inspired by the stringed instruments of Baroque chamber music, building on a foundation of four sizes of Bolivian traditional stringed instruments, brought into existence an entire family of charangos: soprano, tenor, baritone and bass.

The charanguero, in his zeal to preserve folkloric tradition and ancestral wisdom, works with suitable materials until the instrument gradually takes form in his hands with its own peculiarities appropriate to the Bolivian cultural heritage, as are the charango khirki, whose sound box is made from the shell of the quirchincho, the Andean armadillo, that shaggy little animal that gives its life for art and music. It’s not casually that the poet Oscar Alfaro says in verse, "When Don Quirquincho died he bequeathed his heart and soul / as proof of his affection / to the Indian of our people / who clasped it in his hands / and gave it a new life / in the body of a charango / and a soul of melody.”

Its face, fashioned from the wood of naranjilla, cedar, or weeping willow, has a little round mouth through which it laughs, sings, shouts, weeps, and screams, to the heartbeat of the one vibrating the strings and caressing its curves. That's how nicely the charango behaves in the hands of Ernesto Cavour. Confiding in it with trust and affection, he'll say, "papacito, wawita de pecho, llok'alla bandido, maestro pataiperro” (little daddy, suckling baby, naughty kid, street maestro). Cavour knows when he strums the strings that this instrument crossed by strings from one side to the other isn't dead wood but lives and breathes. That's why he takes better care of it than of his own life, wraps it in his woolen aguayo shoulder bag, keeps it under his poncho or stores it in a leather case, not only to avoid its having a mishap or getting out of tune, but also to avoid its falling in love with another owner.

By the same token, he knows that it's harder to master a charango than to tame a wild colt. Not in vain does he say to it "How many think themselves your master, not suspecting that you master us.” No wonder that it isn't easy to deal with the charango, because in addition it's jealous and treacherous if someone gropes it to the point of annoying it more than he should, as if it were any old object. No, Sir! Just so you know, the charanguito, whose strings conveys the vibrations of its soul, is so genuine that it sings and cries tears only in the hands of one who seeks it with sincere affection, more with feeling than because he wants to show off. Ay! If the charanguito could speak with a human voice it would also tell us, between the plucking and the strumming, about the adventures and misfortunes of its life.

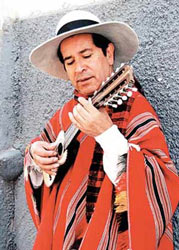

In this photograph, taken someplace in La Paz, Ernesto Cavour, poses with hat, poncho, and a scarf around his neck, displaying the air of one who masters the secrets of his beautiful, unique instrument, which here looks flawless against his chest, the dark sound box under his right forearm and the fingerboard suspended from his left hand. This virtuoso of the charango, possessing skillful hands and deep interpretive emotion, has sought to demonstrate on the major stages of the world that the charango is something more than a simple accompanying instrument.

From the conversation between his fingers and the strings emerge huayños, khaluyos, carnavalitos, cuecas, trotes, bailecitos, ch'utunquis, pasacalles and an endless number of sweet melodies that only this giant of Bolivian music is capable of coaxing from the mouth of the charango, following the lead of the master Mauro Núñez, the notable musicologist and instrumentalist from Chuquisaca, who learned to give birth to charangos and then converse with them as equals with the humility and simplicity of the Indian who gave life to one and cared for it, whether in good times or bad, like his smallest and most beloved son.

With this same instrument that sings to you of life, death, love and love lost, this famous charanguista, recognized as an interpreter of infinite possibilities, recreates the noises in nature and the voices of animals. It isn't unusual for his charango, tuned with the ear of a cat, to imitate the warbling of birds, the braying of donkeys, the bleating of sheep, the lowing of cows, the roaring of lions, the neighing of horses, the locomotive’s whistle, the boat’s horn, the blowing of the wind, and, if someone requests it, even the moaning of the beloved woman.

The Bolivian charanguero doesn’t tire of inventing instruments that are more and more dazzling and sophisticated. Fantasy flies from his hands, and the love of the profession is dignified by artists like Cavour, who, thanks to his social commitment, carries the charango like a rifle across his chest to wherever the public dictates. Sometimes, seeing his comrades scattered far and wide over the world, he sheds tears to the rhythm of his charango; other times, ready to declare his critical spirit, he acts in scenarios where his charango interprets the popular clamor for justice. His presence doesn't pass unnoticed, not even if assemblies erupt in chaos. That's what happened on one occasion; he had scarcely come on the scene, when whistling and booing began to drown out the incendiary discourse of the orators; the crowd, impacted by his presence, became suspended in silence: Cavour said not a word, but their seeing him with the charango in his hands, like the arbiter with the whistle in his mouth, was enough to put an end to the jeering and return to silence what belongs to silence.

Doubtless, this guru of Andean music, who learned to converse with the charango at the age of 12 and found his place with natural authority at the top of the best masters of stringed instruments, will never fail to surprise us with his sensitivity and his professionalism. But not only is he capable of converting everything he touches into music, he is also able to demonstrate that an artist can give his life to art, by giving his heart transformed into melodies.

___________________

VÍCTOR MONTOYA nació en La Paz (Bolivia), en 1958. Su infancia y primera juventud discurrieron en el pueblo minero de Siglo XX-Llallagua, al norte de Potosí, donde se descubrió la veta de estaño más grande del mundo. En 1976 fue perseguido, torturado y encarcelado. Permaneció en el campo de concentración de Chonchocoro-Viacha hasta que, en 1977, fue liberado tras una campaña de Amnistía Internacional. Desde entonces reside en Suecia donde se dedica profesionalmente a la escritura.

![]() montoya [at] tyreso.mail.telia.com

montoya [at] tyreso.mail.telia.com

![]() Más artículos del autor:

Pulsa aquí

Más artículos del autor:

Pulsa aquí

*

IMÁGENES: (Cabecera artículo)

Charango strings played 1, By Elvert Barnes

from Washington DC, USA (Flickr) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)],

via Wikimedia Commons | (En el texto; orden descendente)

Bolivian charango 002, By Villanueva (Own work)

[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons | Fotografía de E. Cavour remitida

por el autor del artículo.

![]() Original

español ▫

Original

español ▫![]() Versión inglés ▫

Versión inglés ▫

![]() Versión francés ▫

Versión francés ▫

![]() Versión

en italiano ▫

Versión

en italiano ▫

![]() Versión

en alemán ▫

Versión

en alemán ▫![]() Versión en sueco.

Versión en sueco.

▫ Artículo publicado en Revista Almiar, n.º 52, mayo-junio de 2010. Reeditado en junio de 2019.